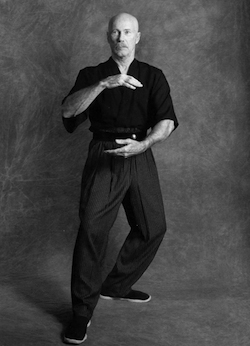

Ken Van Sickle, a native of New York City, is best known for his work in recording images of film and video of Cheng Man Ching, who he was a student of from some years. However is sword skills are exceptional and he has produced an excellent DVD and is currently working on a book on the subject. We are working on an article series about Prof. Cheng Man Ching right now. This will include an in depths video interview with Ken van Sickle as well. See the links below this article as well.

WHAT DID IMPRESS YOU MOST ABOUT MASTER CHENG MAN CHING?

First of all, he was the most relaxed human being I ever saw. At the same time his mind was always active, always doing something, he was at all times “right there”, never disconnected from present reality.

Although he is well known as the “Master of five excellences” (Medicine, Poetry, Calligraphy, Painting and Taijiquan) he was really an all-round personality whose abilities went well beyond the boundaries of those five arts.

He also was very open and friendly in his teaching. We know from people who studied with him in Taiwan that there he was rather aloof and dignified, as a traditional Taiji master was expected to be by that environment. When he settled in New York City he felt and enjoyed the completely different culture and changed accordingly. A notable example of this change is that Cheng Man Ching taught taiji fencing only in the United States, which raised some perplexities among his former students in Taiwan…..

IS THERE ANY “CORE TEACHING” FROM CHENG MAN CHING THAT YOU WOULD LIKE TO POINT OUT?

Not really a teaching , rather a way of teaching: Cheng Man Ching was really able to teach through body contact; it was not unusual for me to feel informations emerge from my body some time after practicing with him, although at the moment I had not understood what he was doing…. and at all times he really did what he said he was doing!

CHENG MAN CHING’S PUSH HANDS DEMONSTRATIONS ARE FAMOUS AND WELL DOCUMENTED. CAN YOU EXPLAIN WHAT DID IT FEEL LIKE BEING PUSHED BY PROFESSOR CHENG?

You felt like being lifted by a big wave, you could not feel the pressure or push in any particular part of your body which was moved as a whole; it was very powerful but neither harmfull nor unpleasant. Actually Master Cheng never did Fa Jin (explosive manifestation of force), although he obviously could, because it can be very dangerous, especially if the force wave travels through internal organs. He rather did what is known as Ti Fang (“lift and let go”), or “uprooting”. Ti Fang requires sensitiveness and ability to tune in with your partner’s natural neuro-muscular reactions, and was done as follows:

First he lightly touched his partner and delivered a very slight pressure, which generated an instinctive wave of resistance. Precisely at that moment he released completely, yet without disconnecting, causing his partner to feel as if falling into emptiness and first sinking forward looking for support (which was not found since Cheng remained loose and relaxed) then unconsciously springing back from the front foot to regain balance. At that moment Professor Cheng sank into his partner accelerating him backwards into his back foot until the pressure made him pop up from the ground. Sometimes he sank very long into his partner maintaining his body loose and letting his own arms bend, then suddenly reconnected his structure, thus creating a particularly strong pressure. Only then his arms extended to follow the partner, he never used his arms to push.

YOU OFTEN REFER TO THE TAIJI SWORD AS THE “FEATHER SWORD”; WHERE DOES THIS EXPRESSION COME FROM?

It is something Professor Cheng used to say: he talked about handling a wooden sword or even a feather as if it were a razor-sharp steel blade until a steel sword felt like a feather in your hand……

AT WHAT LEVEL OF TAIJI PRACTICE WOULD YOU ADVICE BEGINNING FENCING?

Some good basic training in the solo form and push hands is essential, a student can enjoy fencing only when the attitude to relaxation and listening has developed. From this point of view any internal system of training, regardless of the name of the style, is a good base.

Remember that even experienced students will become very awkward at their first attempts to handle a sword, let alone practicing with a partner. In fact it takes quite a time before the sword really feels like a living extension of one’s body.

WHAT IS THE RELATION BETWEEN THE SOLO SWORD FORM PRACTICE AND THE FREE SYLE TAIJI FENCING?

The form helps to develop the correct dynamic connections between your center and the different parts of the sword (grip, center of balance, point) until the sword begins to feel like an extension of your body. Then, the sword form is a repository of fencing and combat techniques, almost everything we do in fencing is in the form. Cheng Man Ching did not explain much about the applications of the moves of the form, perhaps to some of his earlier students. What happens is that, after you have practiced the form and the free style fencing for a long time, the applications seem to manifest themselves very naturally.

ARE THOSE APPLICATIONS REALLY EFFECTIVE?

The Yang Style Sword form that we now practice is an evolution of an earlier form called Michuan, originally taught by Yang Luchan; Michuan was treated as an “inner family” tradition as opposed to the “public style” that was openly taught later by Yang Luchan himself and especially by Yang ChenFu.

Michuan was clearly combat-oriented and its movements and techniques were more straight, while the “public style” manifests more clearly the Taiji principles through circular and spiral movements. The fighting value of the “public style” form was questioned by some, as if were just a sweetened exercise for educated gentlemen and ladies; in reality the correct application of Taiji principles makes it as much combat effective as the earlier style.

DOES A REAL STEEL SWORD HELP IN THE FORM PRACTICE?

It certainly helps to refine the quality of your movement; the weight of a steel sword forces you to lead with your center and to find your best relaxed condition throughout the form. If you use too much contraction and arm force you will feel sore and exhausted after a few moves! Therefore I advise you to try it occasionally at the beginning, increasing frequency as you become familiar with it. Another helpful training tool is a tassel attached to the sword pommel: when the flow of you movements is correct it will dance, following your sword, but as soon as you do something wrong it will twine around your wrist and hand.

IN THE JAPANESE SWORDSMANSHIP SCHOOLS THEY OFTEN PRACTICE TEST- CUTTING OF BAMBOO SHAFTS OR TIGHTLY BOUND STRAW. DO YOU THINK IT CAN BE USEFUL FOR TAIJI FENCING STUDENTS?

Cutting a real target is a crucial test for the correctness of your technique, provided that you have long enough experience in the art, it is not certainly for beginners; you can practice with tree branches (please, not live trees!) or any other suitable material. If your alignment is not correct, if the grip is too loose or wrong-angled, if the whole move is not flawless you can hurt yourself. A good cut is clean, quick and, as it were, effortless.

If you don’t have a Chinese sword (Jian) adapted for real use, a good machete will do.

WHAT ARE THE MOST ESSENTIAL PRINCIPLES OF TAIJI FENCING?

Taiji fencing respects the principles of real fighting, therefore self-defense comes first: attacking is always subordinate to the protection of one’s body; practically speaking, the very first thing you have to learn is to have your blade between your body and your opponent’s blade most of the time.

The second principle is to maintain constantly a sensitive contact between your sword and the opponent’s and train to feel his force, energy and intention through this connection.

The third principle is to “get out of the way” when an attack comes straight towards you: never try to block an attack, that would be using force against force, and is opposite to the “yielding” principle; you should rather move your body just as much as needed to reach a safe distance, without overextending in any direction, and immediately reconnect with your opponent’s blade.

Circular movement is what supports those principles: always circle your blade around your opponent’s blade. It goes without saying that the circling of the sword is led by the movements of the center of your body. You also have to learn to move your body in a circle around your opponent, like Bagua Zhang walking.

HOW DO YOU TRAIN THE CIRCULAR MOVEMENT OF THE SWORD?

The main basic drill is called the “still-point” exercise, in which you move the sword in circles while keeping the point ideally still in front of you. First you move back and forth in half circles, then you learn to do full circles clockwise and counterclockwise. All movements are generated from your center which is connected to the center of the sword (that is its center of balance), while you let your arms and shoulders loosen.

In this way you also train another principle that is: try to keep the point of your sword directed to your opponent’s centerline and threatening him. From this principle it follows logically that you never try to attack while your opponent’s blade is threatening you because you would be immediately hit.

WHAT IS THE MAIN PURPOSE OF THE SWORD CIRCLING?

The purpose is to stick to your opponent’s blade and follow him listening to his force and intention (Ting jin, or “listening energy”); you never push or press on your partner’s blade, rather you look for any excess or deficiency on his part.

CAN YOU EXPLAIN WHAT YOU MEAN WITH “EXCESS OR DEFICIENCY”?

An example of excess is when your partner presses on your blade in any direction: this gives you the energy required for attacking; you move in the same circle and direction, then narrow the circling into a spiral that leads your blade to touch his body. This is an application of the Taiji principle of gathering the opponent’s force to your advantage. Feeling the changes in pressure through the sword is the basic level of Ting Jin for fencing.

An example of deficiency is an undue opening of the opponent’s guard, or even a slight fading of his attention: in this case you should immediately attack, it must be a split-second automatic reflex. You can train this while fencing with a partner by suddenly opening guard without any prearranged pattern; whenever one opens the guard the other must immediately attack.

WOULD YOU SAY SOMETHING ABOUT THE QUALITY OF “INTENTION” THAT SHOULD BE CULTIVATED IN TAIJI FENCING?

The quality is the same we look for in taiji push hands, so I will just mention some issues that are particularly relevant in the fencing context.

First of all “move sincerely”: commit yourself to the action you are performing, so that your partner receives something substantial rather than an external gesture, this influences deeply your instinctive body reactions and the forces involved. This also mean that you should never “feint” in the sense that any action must be supported by a real intention, otherwise the reaction that you expect from your partner will not take place.

Be ready to accept any opportunity that your partner offers you to cut him: it is a precious gift and it would be impolite to refuse it; you can show your gratefulness by cutting him softly, gently and with a smile. Taiji fencing requires a deep respect for your partner’s body, so you never hit hard; safety is essential for fully enjoying this practice. In forty years of fencing I saw one nicked tooth, a cut on the head and some bruises on wrists, which is a very acceptable injury record as compared to other martial styles and sports. One thing that can help you to become more accurate and safety-oriented is to handle your wooden sword as if it were a real steel sword, with the same respect and carefulness required by a live blade.

Finally, I must mention the first and worst “sword disease”, that is the desire to win; this can slow down your learning or even cut you off the flow of deeper information coming from your teacher and your own body.

WHAT SHOULD YOU LOOK AT WHILE FENCING?

At the beginning you need to concentrate your vision to prevent your mind from wandering, so you will look at the swords, or at your partner’s eyes, but later on you will develop an overall vision, which is much better because any particular concentration point can easily trap your mind there. The key word is “stay centered”: if your opponent attacks you and your mind goes to the point he is threatening, the rest of your body will remain unguarded and open to be cut.

HOW DO YOU USE YOUR UNARMED HAND IN FENCING?

The left hand is essential, as in any other Taiji form of training all parts of the body must be fully connected to the center. First of all this hand constantly counterbalances the sword hand. Besides, it can be used, if the opportunity arises, to take control of your partner’s sword hand and simultaneously attack him with your blade. For this reasons you should never let it hang down limp, it must be a live hand: it is best kept ready for action in front of your body, the arm maintaining a round shape, carefully preventing your elbow to stick to your chest; pointing your index and middle finger to your sword hand wrist can help to get the correct posture.

WHAT IS YOUR OPINION ABOUT TAIJI FENCING TOURNAMENTS?

I am not particularly in favor of the way push hands and fencing tournaments are conducted, the overall level is not good enough and the rules keep changing, so most people end up into using brute force rather than taiji principles. Protective gear can even worsen this, although good for the physical safety of fencers. Cheng Man Ching was always playful and smiling while fencing, and we should try to keep this spirit alive.

Original article and pictures take taiji-forum.com site